There was no

Paris bulletin in March because from early in the month I was in California.

Six weeks later and I’m back, battling my way once more through the milling

crowds, side-stepping the beggars and trying not to notice the disks of

chewing-gum hard-pressed into the tarmac and the quantities of cigarettes butts

in the gutters. The State of California may be inviting its citizens to ‘make

California smoke-free’, but back here in dog-eared old Europe the tobacco

companies have as yet nothing much to worry about.

There is no

point trying to draw comparisons between northern Paris and southern California

however. The two are so remote in every respect that, beyond noting that both

places are heavily shaped by the industry and inventiveness of human beings,

there isn’t a lot one can usefully say.

The French

have just voted – in larger numbers than expected – in the first round of the élections

présidentielles. The run-off will pit the Right (Sarkozy) against the Left

(Hollande) – concepts which still have some currency in Europe but practically

none as far as I can see, in the US. While I was there Mitt Romney inched

further towards securing the Republican nomination against Obama, although for

some, putting a wealthy Mormon in the White House seemed to stir up almost as

many anxieties as the prospect of a Black President did. Here all the talk is

of the way in which the Front National, which polled an alarming 18.6% of the

vote, is shaping the discourse of the second round.

Nothing to do

with Romney but on one of our Californian outings, we went to take a closer

look at the Mormon temple of San Diego that you can see as you drive south on

the I5. As the photo shows, it is a Disneyesque edifice of bright

white concrete. With its menacing sharp angles and sterile surroundings it looks

exactly as if someone has brought the Snow Queen’s palace all the way from the

frozen north and dropped it down among the cacti and succulents. As we wandered

round the grounds (we were forbidden entry to the building itself, not being

‘clean’), an image popped into my head of the tiny mosque in the street right

behind the flat here, the scuffed doorway and the pile of men’s shoes kicked

off on the pavement outside.

While I was

away a Scottish friend sent me a lovely book, ‘The Most Beautiful Walk in the

World’ by an Australian-American, John Baxter. It is, as its sub-title

indicates, (‘a pedestrian in Paris’) another affectionate account of what a

well-to-do foreigner - living on the Left Bank, it goes without saying – finds

most appealing in this city. Baxter lives on the rue de l’Odéon, ‘which’, as he

tells us, ‘is to literature what the Yankee Stadium is to baseball’ (note the

comparison, a dead give-away for who he thinks will buy his book).

There are of

course many other streets and quartiers in Paris as imbued with powerful

literary associations as those Baxter claims for his street. The point is

though, that no 12 rue de l’Odéon was the one-time address of Shakespeare &

Company. That English language bookshop, owned and run by East-Coast American

Sylvia Beach, had from the outset all the ingredients the romance-seeking,

literary-minded American tourist could desire: a love affair between two women (Adrienne

Monnier and Sylvia Beach were lovers for over 30 years) and a whole stack of

famous or rapidly becoming famous writers, such as Scott Fitzgerald, Hemingway

and Joyce. It was Beach who had the courage and apparently the financial means,

to publish Joyce’s Ulysses in 1922. Heady stuff for the Americans who came between

the two world wars, to what they still like to call ‘the City of Light’, to

study and dream - and write their own stories.

The original Shakespeare

& Company closed long ago. Beach was forced to shut the shop during the

Occupation and although Hemingway symbolically re-opened it in 1944 it never

traded again.

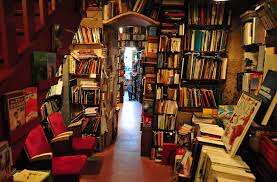

It was left to

another American, George Whitman, to bring the whole thing back to life, albeit

in a different place, a higgledy-piggledy old building right opposite Notre

Dame on rue de la Bûcherie. Beach bequeathed to Whitman both the name of her

shop and a good many of her books. Those and the income from the ever-larger

numbers of Americans arriving in Paris and wanting to buy a bit of that heritage

for themselves have ensured that the shop has prospered ever since, without so

far having to relinquish its original ideals.

Two years

after the new Shakespeare & Company opened in 1951 Lawrence Ferlinghetti followed

Whitman’s example – Whitman and he were friends – and opened the City Lights

bookstore in San Francisco, thus sealing another link between the Beat

generation and their Parisian counterparts. Having now spent time in both bookshops

I can confirm that they are equally well-stocked but that Shakespeare &

Company remains unique as far as layout, hospitality and idiosyncrasy are concerned,

incomparably more shabby, dusty and down-at-heel but with a vitality that gives

one some small hope for the endurance of the printed page despite the rise and

rise of the electronic book.

Shakespeare

& Company is a ‘must see’ site for all sorts and conditions of visitors to

Paris. Once upon a time when I was young and living the Left Bank romance

myself it might have been for me too, although as it happens it never was. Now

I’d give it a passing but affectionate mention in ‘my version of Paris’. That’s Paris for you, as John Baxter says,

more than almost any other city, a blank sheet on which each of us writes our

own script, draws our own map.

No comments:

Post a Comment